Kenmare ND - Features

Real People. Real Jobs. Real Adventures.

Thanks for reading some of the latest features about area people and events.

To view every page and read every word of The Kenmare News each week,

subscribe to our ONLINE EDITION!

Lloyd Holter was on the road in Korea during most of his service

For Lloyd Holter of the Coteau area, the Korean War began in September 1951, when he was drafted into the 25th Quartermaster Company. The 23-year-old completed his basic training at Fort Knox, Kentucky, and shipped out to Korea in January 1952.

11/06/13 (Wed)

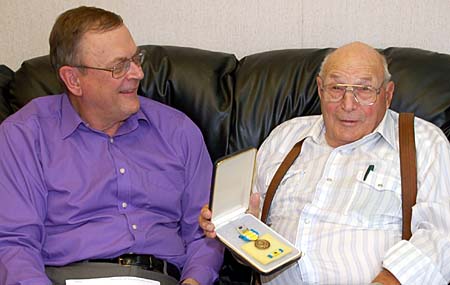

60 years later . . . Lloyd Holter receives his Korean War Service Medal and Ribbon

60 years after the end of that war in July 1953. He shares a smile and memories

about his months spent driving U.S. Army trucks with friend John Steinberger

in Kenmare. Holter attained the rank of sergeant in the Army.

By Caroline Downs

For Lloyd Holter of the Coteau area, the Korean War began in September 1951, when he was drafted into the 25th Quartermaster Company. The 23-year-old completed his basic training at Fort Knox, Kentucky, and shipped out to Korea in January 1952.

“I was in the truck pool, then I went into the mechanics pool besides,” he said. “I put in my time.”

Holter said he’d done plenty of driving at home up to that point, so handling one of the Army’s trucks didn’t intimidate him.

Neither did the mountainous landscapes, the intense snow and cold of the Korean winters, and the narrow trails he had to navigate. “There was a lot of tough road, but nothing that ever scared me,” he said. “I was used to all of it from home.”

Holter spent most of his time in Korea behind the wheel of a 1945 Chevrolet 2-ton truck, without a heater. “Mine was a big truck,” he said about rig No. 1928, adding he was actually certified to drive anything up to the five-ton models. “There wasn’t nothing I couldn’t drive.”

He often led convoys of 15 to 20 trucks, although occasionally he would make a trip with just one or two other vehicles. “I ran almost every day,” he said. “It was very seldom that I wasn’t out on the road somewhere.”

His loads included American and South Korean troops, as well as a variety of supplies for the front lines. “I hauled more equipment than anything else,” he said. “Whatever had to be moved, I was hauling.”

That meant he transported ammunition at times. “Yeah, if I’d been hit, that could have blown any of it,” he said. “I never worried. We carried a lot of ammunition and other drivers worried, but I didn’t.”

Holter was trained to protect himself from enemy attack, but other than fighting the road and weather conditions, he was never challenged. “I had my rifle with me, sat right alongside me in the truck,” he said, “but nobody ever tried me.”

He also traveled with one or both of the small mixed-breed dogs he raised in camp from puppies. The 15 soldiers sharing his barracks, a double-walled tent to which they’d been assigned, helped care for the two pups.

“I kept them as pets and they were fed the same as I was,” he said. “Most of the time, they were in the truck with me.”

He continued, “They went everywhere with me, and they protected me.”

Holter entered the service with acquaintances from Killdeer and Columbus, although the group did not stay together. Sometimes, on that other side of the world, he’d run across a man he knew from North Dakota.

“My brother Howard was drafted about a year later, into a different division, but I’d see him every once in a while, too,” he said.

He primarily focused on his truck and his next haul job, often working in stretches of three weeks with no time off and little sleep. “What are you gonna do?” he asked. “You serve your time and get the heck out.”

Holter served as a corporal for nearly a year and was promoted to sergeant before he returned to North Dakota. “I did my job, is all,” he said of his accomplishments.

Shortly after the war ended in July 1953, he made the three-week journey back across the ocean to California, arriving in the United States with only his work shirt, pants and boots after his bag was lost, or stolen, on the ship.

He was sent to Fort Lewis, Washington, where he received discharge papers and boarded a train for Stanley.

Once he arrived home, Holter immediately started work in an all-too-familiar position. “They were building road then, the Number 8,” he said as he described the highway between Stanley and Bowbells. “My dad was working up there and he said they needed a driver, so I hauled dirt and rocks for them.”

“And he has worked ever since,” added his wife Mariea, who was merely a younger girl in the area at the time Holter left for Korea.

However, Mariea faithfully mailed letters to him while he was overseas. “He was our neighbor,” she said. “My cousin and I each picked someone to write to during the war.” Those letters eventually sparked a romance.

Despite the hardships of his assignments and harsh living conditions, Holter didn’t resent his military service.

“I did a lot of work, and I did a lot of what I enjoyed,” he said. “I took care of myself and that was all I could do.”

*Read about Jerry Rasmusson's and Gerald Lawson's Korean War experiences, too.